Colorado recently passed an expansive version of a state-run paid family and medical leave program. The benefits are alluring, some say a moral imperative. Yet there is growing evidence that this policy model is failing to fill its primary objectives. It is not clear that it is advancing equity for working caregivers. Of even more concern, there are innumerable doubts as to whether a government program on this scale will be sustainable. It matters because once a critical number of decision-makers decide that it is no longer sustainable, the destabilizing effects will be felt across the economy.

Advocates claim with confidence that the program will be solvent. What they have taken on is much bigger than they realize.

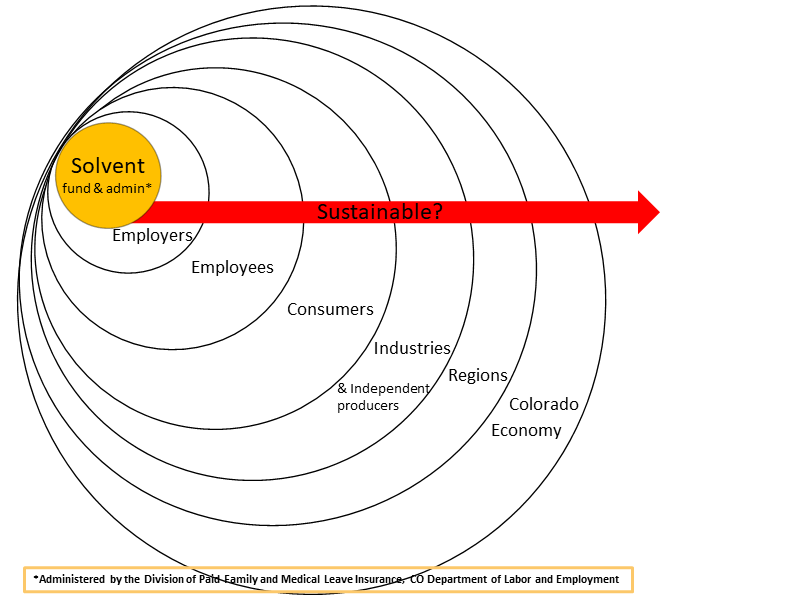

Proponents of this approach have addressed any objection over sustainability by advancing instead, an argument that the government program will be solvent. Solvency and sustainability are dramatically different in scope. Fundamentally, one is isolated and measurable and the other resists efforts to quantify broad and spreading impacts.

The overarching goal of a government paid leave program is to intercede and take over the management of an employee benefit. Of significance is that these benefits are tightly intertwined into the operations of any business that relies on labor. The inevitable result is that many of the costs, both direct and indirect, are off-loaded onto those businesses.

This will have a number of secondary impacts – significantly, on jobs and wages, and ultimately, sustainability. Proponents reject the concern for those costs. They have waved off efforts by the business community to explain how this policy, when put into practice, will have negative impacts on businesses and their workforce. Their models tell them that this should work.

It is the dismissed business community that must daily navigate complex and ever-changing realities. They understand the weaknesses of these models in the face of what cannot be measured or predicted.

Yes, solvency of the program is critically important, but it is ultimately sustainability – the longer term question left unanswered – that has the greatest impact on the economy.

First, what does solvency look like?

Solvency must be determined by the agency overseeing the fund and its administration. They must balance the tax revenues with the expenses of the program.

- Revenues are captured through the payroll tax deducted from employees’ wages including a matching contribution from employers. 1

- Expenses include the outlays to cover the wage subsidies for workers who submit an application for a qualifying leave of absence and the various expenses of the administration.

- Administrative costs range from processing claims, distributing benefits, adjudicating conflicts, enforcing compliance, education and outreach.

“Eight other states have made this program solvent.” – Senator Faith Winter in a discussion, on Colorado Decides.

Colorado Senator Faith Winter, among the most prominent proponents for government-run paid leave, claims that the 8 states that have passed similar mandates are solvent. That seems an unusual claim since three of those has not fully launched their programs. It cannot yet be determined if these are solvent. They are not fully operational – accepting claims and paying out benefits.

It will take several years to determine solvency thresholds. At the very least, after one year of paying out claims and administrative expenses, the math must add up. Those expenses must be covered by the payroll taxes pulled from the wages and compensation of workers.

Colorado will not see any minimally measurable results until 2025, one year after final implementation. WA, a new pfml state, not until 2021. Those results may have questionable value after a year distorted by COVID’s impact on employment. It has been a year marked by wage subsidies and labor market churn.

Three states are still bringing up their programs. Those first-year results will be evident for MA in 2022, CT in 2023, OR in 2024.

CA’s current results reflect more modest programs. As recently as June 2020, their paid family leave allowed only 6 weeks. July 1, it jumped to 8 weeks, and Jan 1, 2021, it will jump to 12 weeks, only then offering what Colorado plans to offer. First-year results for California’s 12-week program and other recent expansions won’t be clear until 2022. Their payroll tax is already at 1%. They claim that the family leave is a relatively small percentage of their overall program which includes medical leave, but it is a rapidly rising portion. NJ and NY have similarly had recent expansions.

The math must add up. Each state must reevaluate its readiness for the next year. They must make a decision about the adequacy of the current payroll tax to capture the required revenues. This projection is made harder by the changes as a result of growing program popularity and familiarity with the terms by workers in the workplace. Claims will increase as workers become familiar with the broad opportunities to take a leave and how and when to access the benefit. How much more use can these administrations, responsible for processing claims, expect? It is a calculated guess that is particularly volatile in the first few years of the program.

Advocates further step forward with the bold claim that rates will likely go down.

“And we expect the amount (the premium) to go down. In the 8 other states that have this, they have been so solvent, they have expanded the program. So we are confident that this is the right amount to create a solvent program. It could go down in the future. And we believe it is going to be a strong program for Colorado.”

-Senator Faith Winter, Colorado Decides.

“The bipartisan actuarial study shows that this is a solvent program.” 2

-Senator Faith Winter, Colorado Decides.

An actuarial study is not all science. It is an effort to provide guidance in the face of uncertainty. Every study involves a certain amount of judgment which the actuary reveals and defines in their evaluation. The Colorado FAMLI Task Force was convened to direct an actuarial study for Colorado. It was acknowledged by task force members that the data the actuary had to rely on was far from ideal. Experience from other states was quite variable and their ongoing changes blurred efforts to assess reliability. There are a number of reasons that suggest assumptions of predictable growth are unsound.

Here’s the problem with focusing on solvency without acknowledging the risks that lie beyond: a program design that relies on a payroll tax can always be made solvent.

Regardless, what does “solvency” mean? A government fund can always be made solvent by increasing the payroll tax on workers. It is essentially a math problem when taxpayers are captive.

Once a significant number of workers reject those increases, lawmakers will turn to other levers in the framework to shift that burden onto high-wage workers. Options include raising the limit on wages subject to the tax or turning to other forms of taxation to target fund relief. This would place the tax burden on a broader number of taxpayers in Colorado.

This 16-minute video covers a lot of territory concisely. Kristin Strohm, President & CEO of the Common Sense Institute, explains the top-line concerns for the Colorado measure that did pass in November. The discussion digs a little deeper below the surface and challenges the assumptions by advocates. Similar concerns will face all states considering this newer more generous model.

The more pressing question should be, “Is the program sustainable? At what cost?”

On its own, solvency is a dramatic oversimplification that assumes the pfml program – its fund and administration – exists in isolation.

Sustainability is a much broader topic. It is harder to measure. It is an assessment made by the multitudes, each in their daily lives, over time.

Sustainability is in the eyes of the beholder

There are a number of spreading consequences of the policy that are difficult to identify and trace. They impact each individual differently.

How much can employers sustain? This is a critical open question. The impact of not only the payroll tax but the impact of the terms and compliance are unequal depending on the nature of their operation. There is wide concern that small firms can not bear these terms.

What do workers as individuals consider sustainable? How much of a deduction from take-home pay is too much? Someone that expects to use the benefit more frequently may feel the sacrifice is fair. In fact, it might be quite a bargain. Yet it may also create barriers and a loss of opportunity for those who are at the margins or who lack skills.

Those who have limited needs or who already had this benefit or a similar one may feel that the mandated and defined benefit has implications – either for their other benefits that may have been less restrictive or more desirable or because the program has negative consequences on their job and career opportunities.

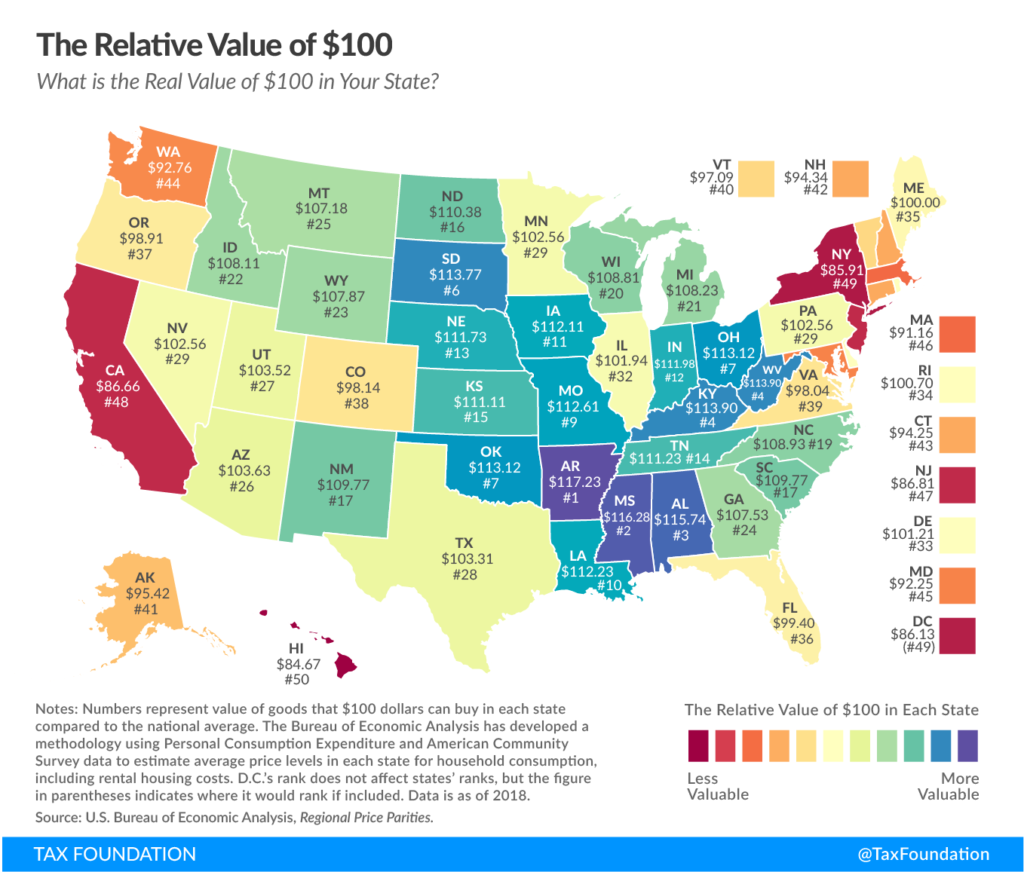

How much can consumers sustain? As labor costs rise, along with the other costs that fall on employers from the spreading impacts of this policy, employers must reduce reliance on labor, reduce wages and benefits, or raise prices for products and services. How much can consumers bear? The states that have adopted paid leave have higher costs of living, likely due to the conglomerated impact of similar policies that centralize decision-making and regulatory schemes and that leave consumers footing the bill through higher prices.

How much can the economy sustain before the impacts on job creators generate enough unknowns to reduce investment or force a reallocation of resources? Progressives have succeeded in passing a number of substantive measures in just the last few years that are increasing uncertainty, labor costs, regulations, taxes, compliance, and litigation risks.

Concerns and doubts about sustainability will travel, hidden from efforts to measure them, like radio waves through the air where they are heard and listened to by those many decision-makers.

What does unsustainable look like?

Because a lack of solvency can be off-loaded to captive taxpayers, it is not the ultimate determiner of policy success. Instead, it is sustainability by the decision-makers in the economy that will determine the policy’s success. And no one will hear those individual decision-makers. Until they do.

Signals are lost.

The purpose of this ambitious scheme is to universally provide full-benefits for paid family and medical leave. When free to operate in the economy, the provision of employee benefits, integrated with compensation agreements, provides clear signals. These shape the field of benefits holistically. Benefits then seek to satisfy the changing needs of both employees and the employers that pull workers into the economy. It is not an orderly or predictable process. It is dynamic and depends on ongoing discovery between the two – employees and employers.

Progressive labor advocates have pushed back on that messy process as intolerable and seek to control it. They are confident that they can craft an ordered framework based on the features of today’s most generous paid family leave benefit in isolation of all other benefits. They expect to force all businesses to fully cooperate and adapt to this framework, regardless of the realities that dictate their unique operation.

By transferring a critical relationship from its more freely operating contexts and burying it in a bureaucracy, there is no one to hear the signals that must be heard.

Will this imposition go too far? How will we know? Where are the feedback loops that will inform progressive lawmakers that their intervention into this critical relationship has succeeded or failed?

We will see the only signals that can be measured – solvency of the administration of the benefit. The government will collect data points from claims.

How will we know when this policy, together with other bold interventionist regulations by progressive policymakers, has reached a tipping point of sustainability in the broad economy? Michael Blastland, in his insightful book, The Hidden Half, claims that much that what is hard to measure is like counting mushy peas. A number of labor and employment focused policies have created constraints for employers and growth. Minimum wage, mandated sick leave, pay equity, anti-harassment, are only a few, and now add the dramatically underappreciated paid family leave mandate.

Signals are lost – until they aren’t

There are a number of factors at work here, but is this the ranking Colorado seeks to achieve?

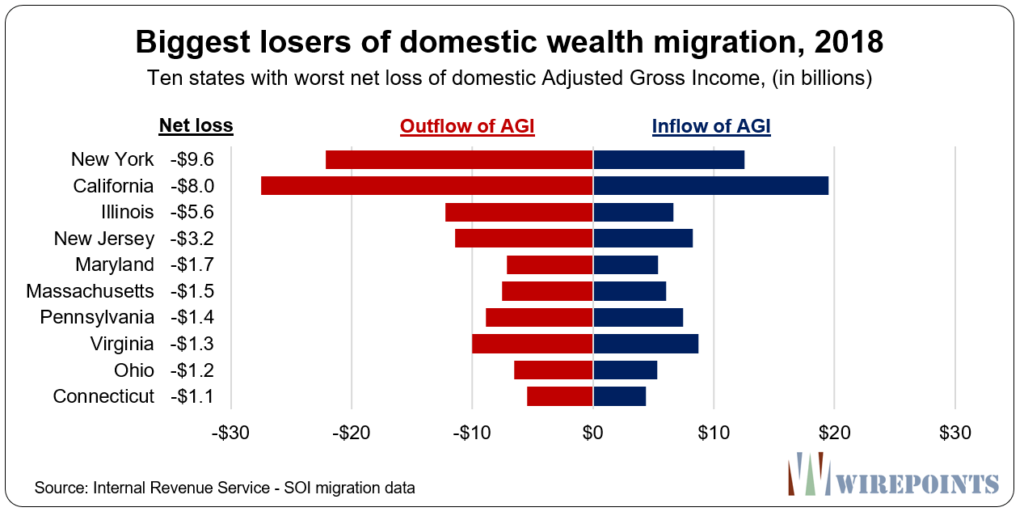

At some point, the suppressed feedback loops and those critical signals, with no one to receive them that has the power to respond to them, aggregate, and eventually emerge. At the extremes, the only remaining decision available is exercised – to escape what cannot be sustained. For families, that might be climbing cost of living or declining wages and job opportunity. For businesses, it is the climbing costs of labor, making hiring and employees an obstacle to avoid, rather than a path to growth. Businesses must pay close attention to the threat of government policies that build a lack of confidence, or too many unknowns. When these together are not sustainable, they must seek a less restrictive or more stable environment.

This is already happening in the states that have preceded Colorado in passing similar policies. Significant signs of lagging policy responses are emerging in those earlier states. California, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut are all bleeding wealth, families seeking prosperity, and businesses. Soon to join that unfortunate outcome will be Washington. They have dramatically reversed course in just the last few years by promoting a rush of harmful policies on an otherwise thriving economy. Colorado sadly seems destined to follow as well.

The bottom line:

Advocates for Paid Family Leave have promoted and passed a highly volatile program. It captures workers, consumers, businesses, and the economy by manipulating what is a fragile and complex network that they don’t appreciate for its interconnectivity and propensity to resist control. It is that broad network that must determine if this policy approach is sustainable.

By shutting out or overpowering other perspectives and concerns, progressive advocates essentially hid those risks and instead boldly claimed that what matters is only program solvency in isolation. They dismiss the weaknesses of the assumptions and data used to support predictability. This is a dangerous over-simplification that will exact its heavy costs on all Coloradans over time.

1 The contribution mix is unique to each states’ program. In Colorado’s new law, the current mix is 50/50 with the option for employers to pay any or all of the employees’ required contribution. Some states have created a more complex formula or divided the formulas and programs. For example, it may require a full contribution by employees for the paid family leave and a different formula for the employees’ own medical disability. Regardless, most economists agree that because the payroll tax is part of the employers’ compensation expense for that employee, most if not all of that contribution is ultimately borne by the employee.

2 The two studies referred to in this YouTube discussion:

- Bipartisan study refers to the study commissioned by the 2019 FAMLI Task Force. The study can be found here as well as the follow-up supplement report here . A broader discussion of the Task Force, its mission and its findings, including links to original documents, can be read here.

- The independent study referred to in the discussion is from Common Sense Institute which uses a REMI model to evaluate economic impacts to support a broader consideration of policy topics and to support more thoughtful policymaking.

Can a Government Paid Leave Program Promote Equity?

Can a Government Paid Leave Program Promote Equity?