The health benefits of family leave are heavily supported and widely acknowledged. Their popularity has driven rising efforts to provide them in the private sector – especially in the last few years. Yet efforts to implement state-run policies have enjoyed mixed success. They require a significant and irreversible commitment, yet costs are still unclear. This makes it difficult for workers to determine the value of this benefit – in context of what is a deeply personal and ever-changing work/life balance.

Big questions are left unresolved as Colorado considers paid family and medical leave.

How much will this grow over time and how will those changes impact program cost?

A Universal Social Insurance Program, which is a state-run community-rated fund and program, is the most prevalent policy model.

Interest is emerging for an alternative, an Employer Mandate. It also requires mandatory participation with benefits and rules set by law and administered by the state. What sets it apart is its reliance on a regulated market of insurance providers rather than a government-administered fund. This option is likely to reduce disruption to existing employee benefits, offer superior service, and may help to control costs.

Programs typically mandate participation and impose a payroll tax on all workers (in some cases with a contribution from employers) that may be set annually to ensure that the program will be sustainable.

Unanswered is the critical question, “Will it be sustainable?” Will workers continue to value the benefit over time as their payroll tax burden grows, reducing their disposable income and diverting employer funds from other benefits? How much and how fast will it grow? We don’t know.

Policy goals in conflict

The policy goals of PFML advocacy groups are diverse. But together they agree that each must increase and expand use for their targeted need and purpose. These include low-income workers, young mothers, young parents, caregivers of elder loved ones, chronically ill, military families, or victims of domestic abuse, violence, or stalking, supporting military families, or those volunteering an organ donation.

In order to promote successful passage, advocates must also claim predictability and affordability. Is it realistic to expect them to deliver both generous, wide-ranging benefits and affordability?

The policy model relies primarily on expected benefits from scale – assuming that affordability will be delivered by a large, state-wide pool. But scale presents plenty of risks of its own and is far from a win/win, as many can attest to. It not only scales benefits but also harm and must be deftly navigated. Does a government agency constrained by this law have that capacity?

Is PFML Predictably Affordable?

The FAMLI Task Force convened by last year’s unsuccessful effort to gain enough consensus to pass a PFML program. It submitted two policy models to an actuary for analysis – one with more generous terms and benefits than the other. The actuary reported two sets of estimates to predict the use rates and costs of those models. Actuarial studies are a valuable tool and decision-makers often rely on them to provide guidance in context of uncertainty.

Can we have confidence in estimates and projections?

It is important to recognize that prediction models are not all science. While they employ scientific methods, ultimately, at some point, they rely on human judgment. For this study on PFML, there were multiple points at which human judgment was required. The actuary selected available data sets and adapted them to a framework of the broad variables that should be the most predictive and projected them on data unique to Colorado’s demographics and economy to estimate use rates of the benefit.

Complexity

The policy structure, even among the top-line variables, is complex and the variables, interconnected. Determining the impact of an orchestra of change is unlikely.

Changing and disparate data

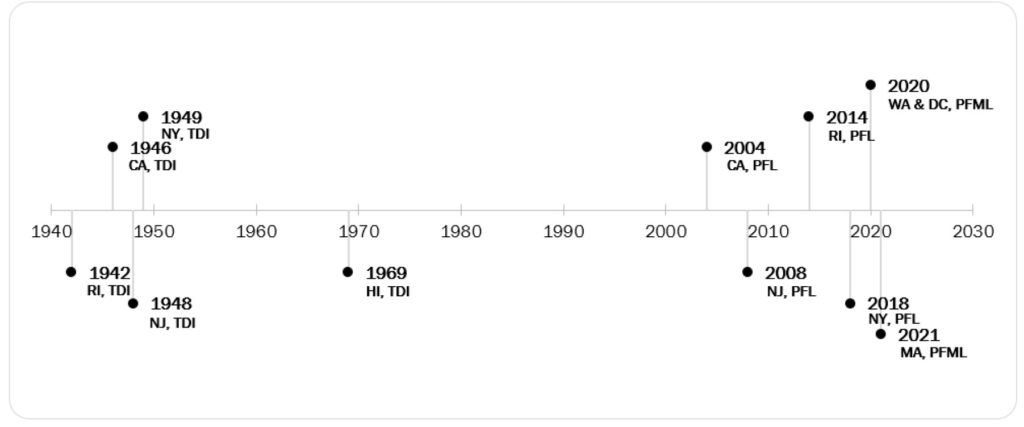

The actuary supported his work with available data sets from the states who have claims and cost experience with their PFML Programs. As you can see in the timeline, California was the first state to implement a paid family leave program. New Jersey followed four years later, Rhode Island, ten years later, and more recently NY, fourteen years later.

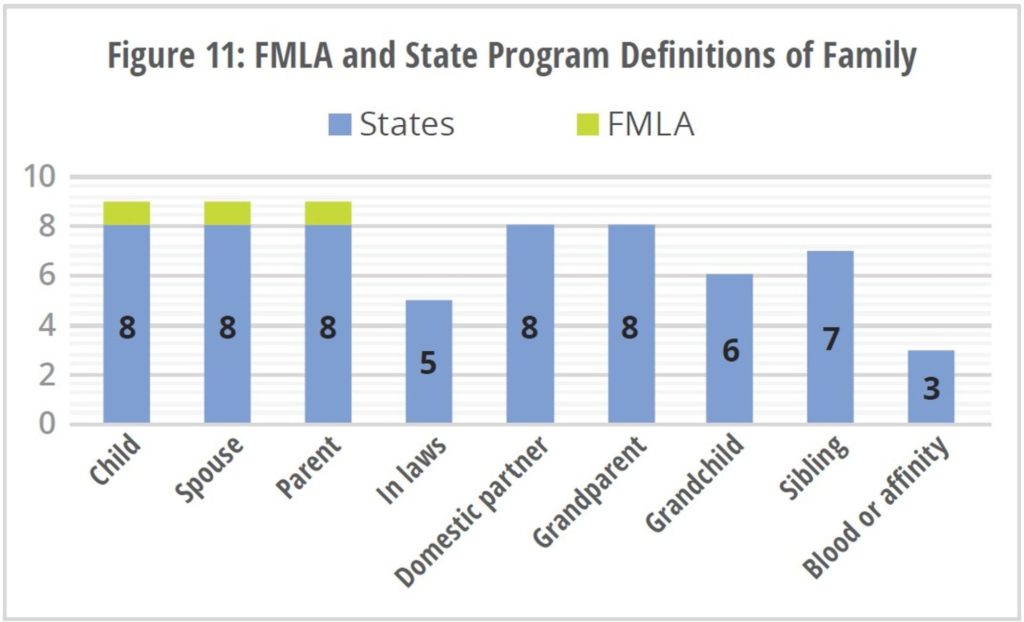

Every one of these programs has differences in their structural framework. Variables can range widely – such as eligibility for the benefit, the scope of relationships, leave durations, wage replacement proportions, and contributions.

Other factors include whether the program is exclusively employee-funded or shared between employee and employer, and the ability of firms to opt-out or self-employed to opt-in. All of these factors and more are embedded in the context of that state’s particular administration and rules.

Only recently these states have expanded and modified their programs to satisfy higher expectations as well as to address disappointing policy outcomes among their target populations. Some of these modifications now approach the generous levels that Colorado has been considering for their program.

Modifications may have included longer leave durations, wider ranges of relationships, lower thresholds for eligibility, and adjusted formulas resulting in higher wage replacement. Policy makers expect these modifications will break down barriers to use for these workers. It is unknown how rapidly use rates will grow as a result of these many changes.

We are still learning.

Several states that are currently rolling out or considering PFML are adopting these more expanded program models. We lack experience data to make critical estimates of the programs’ costs. It would be instructive for Colorado to pay close attention to the early results of states like Washington, Oregon, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

All have passed laws, but won’t fully understand their costs until they begin accepting and paying out claims. Washington will be fully operational January 1, 2020, but the others, not until 2021 or 2022. It will take time to understand the patterns and rates of use. It seems early to push forward with so many uncertainties.

There is lots of room for future growth of the program

Low levels of awareness and the growing need for caregiving leaves lots of room for future program growth

Presumably, after sixteen years, California’s working population must be familiar with the family leave benefit. Yet studies continue to reveal a nagging lack of awareness among the broader population, including confusion over eligibility and the application process.

Understandably, this is a disappointment for both the workers who are paying for a benefit they may be eligible for but not using, as well as for policy advocates, who continue to craft solutions to break down barriers to broader use.

For example, California spent 6.5 million 2014-2017 on an education outreach program, Moment Matter. Awareness is unevenly distributed, with higher awareness in urban areas, most likely influenced by the prevalence of larger firms with active HR departments that facilitate awareness and application.

“Appelbaum and Milkman have provided the most continuous coverage of PFL awareness in California, documenting the awareness of the program in 2004, 20112 and 2013. The most recent research done regarding awareness, however, was completed by the California Field Poll in 2015 and found that only 36% of voters were currently aware of the PFL program. This is a noteworthy decrease from the reported 42.7% awareness in 2011 and the 48.6% awareness reported in 2009.

From a study by Andrew Chang & Company, commissioned by California EDD

Other states have had similar experiences. But today, Paid Family Leave is part of a very active national conversation. Can we expect the same rates of program growth experienced by those earlier states, or will the combination of higher rates of awareness and changing workplace norms lead to higher use? How much higher?

Bonding leave has the wind at its back, and caregiving leave is still in its infancy and vastly under-utilized.

In the private sector, temporary disability, maternity leave, and more recently parental bonding leave have become more prevalent. Caregiving leave is growing in popularity. This relatively new offering is in response to feedback loops that indicate a growing workforce need.

Leave benefits are a critical tool to attract and retain talent. This has led to greater investment in technology to understand worker’s needs and integrating these HR functions into more areas of firm management.

Bonding leave applies to parents of newborns or to adoptive or foster parents. It usually must be used within the first 12 months. Many states allow for intermittent use over that term.

Estimation of its use is made relatively less risky as there are a limited number of variables. The demographics of a state indicate the number of young women of childbearing age and fertility rates, as well as the expected leave duration (most women take the full number of weeks allowed). Yet evolving workplace cultures that support young parents and bonding for fathers has probably impacted use rates in the three states, and so it is not surprising that this take-up rate has accelerated.

Bonding claims for fathers are still significantly lower than bonding claims for mothers. Very few PFL claims are made for foster care and adoption.

California has experienced high rates of growth for the take-up of all family leave benefits. Yet it is believed to be significantly underutilized.

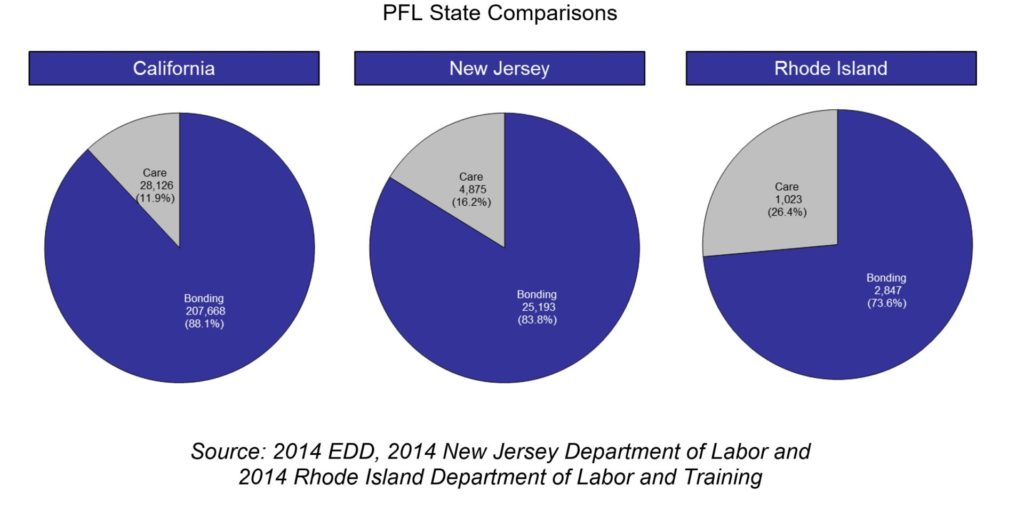

Family caregiving leave, which extends to a wide range of relationships, has still low use rates relative to the others – temporary disability and bonding. Yet there is plenty of need as demonstrated by organizations particularly concerned about caregiving for our aging demographic.

Stakeholders also point out that even though one in six Americans reportedly provide care to elderly or disabled family members, the numbers claiming PFL benefits for providing care appear to be comparably much lower with just 26 thousand claims among California’s 15.7 million workers in 2013.

From study by Andrew Chang and Co, commissioned by California EDD

While an imperfect comparison, it seems reasonable to think that workers would access the program much more as it becomes more widely accepted and understood.

The graph above illustrates the relationship between leaves claimed for the caregiving leave (gray) and the leaves claimed for bonding (blue). These numbers suggest that not even 1% of those part-time and full time working adults who are currently providing care are applying for benefits.

In combination with the projected growth in needs for elder care, it is reasonable to expect significant claims growth for this caregiving leave benefit.

Expanded relationships are intended to support today’s growing caregiving needs.

Which of these many variables has more power to predict the growth rate of use for the caregiving leave? Advocates have confidence in the existing modest claims data and assure us that a concern for unpredicted growth is unwarranted and dismissible. Is that confidence premature?

Job protection in combination with a wage replacement lowers barriers to use.

How much power does the combination of job protection and wage replacement have to impact use rates, particularly among those workers for small businesses with fewer than 50 employees who have not previously had job protection from the federal law, FMLA?

FMLA, the federal law that offers workers legally enforceable job protection, allows workers to take a leave without interference, to expect reinstatement after a leave, and non-discrimination or non-retaliation. It shifts the relationship of accountability almost exclusively to one between the State and the worker.

Benefits offered in the private sector allow for a trust/obligation relationship between the worker and the employer. This gives the employer some discretion to manage their staffing – covering employee absences and hiring replacements if necessary.

We lack data to understand the impact of a legally enforced right to leave, facilitated by wage replacement. How much power do these combined have on business sustainability? The job protection exposes businesses to different levels of risk and costs depending on their size or industry.

An increase in those costs could impact hiring patterns, wage levels and other employee benefits.

California and New Jersey have not broadly extended job protection to employees of small businesses for family leave. New Jersey, for example, in 2019, instituted an extension of family leave job protection to employers with 30 or more employees.

Advocates claim that the lack of job protection suppresses take-up rates among their targets- low income workers, who may lack job security. If that is true, and if we are relying on the experience data from California and New Jersey, would including that in a Colorado law impact use rates? How much?

And finally, not to be ignored are the wild cards:

Human behavior

Woven into every interaction of this complex system from the bottom on up is human decision-making. While many may see it as predictable on a personal level in context with our dramatically different daily lives, is it on this state-wide scale?

Future change that we cannot today even imagine

And last, but certainly not least, unforeseen technological and market changes may disrupt the nature of work. Will they make traditional work models less prevalent? How will a Universal Social Insurance Model, with an established framework of laws and infrastructure change in response? Would an Employer Mandate offer more flexibility?

And will the heavy regulations and rules hinder initiatives to find better more tailored solutions for workers? The trend is toward personalizing benefits. Workers have a broad scope of needs like workplace flexibility, childcare, career education, tuition repayment, and retirement. Innovations like PTO banks, for example, give the worker more personal discretion on how to direct their benefits.

How this policy will impact our businesses and the jobs they support is unknown.

Efforts to modify and expand benefits and to broaden awareness are likely increase take-up rates. Every claim represents an absence in the workplace. The costs of disruption from rising rates of absenteeism are not clear. They are likely to vary widely across business models and industries. These costs are hard to track and quantify making it hard to understand the impacts of broader use and various modifications.

PFML terms impose a particular burden on small businesses that may lack the resources to sustain longer disruptions.

Businesses also face multiple challenges due to other expanding and overlapping employment regulations that raise labor costs. It is unknown how these measures collectively will impact businesses, state economies, and jobs. We are enjoying economic growth that makes risks seem easier to take, yet taking current conditions for granted seems unwise.

This policy is a lot to deliberate. It is big. It is complex and confusing. We all want the best possible outcomes. Is one state-mandated PFML program the right solution for what is a changing and very personal life/work balance for every worker? Is it wise to burden workers without a clear understanding of costs and how they will grow over time? It seems a big risk. Only time will tell.

What can Colorado Learn from Washington State as They Roll out Their Ambitious Paid Family and Medical Leave Program?

What can Colorado Learn from Washington State as They Roll out Their Ambitious Paid Family and Medical Leave Program?