Opponents to a paid family leave mandate in Vermont and in New Hampshire have their governors on their side. Both have explored a state initiated program that would allow private sector employees and employers to voluntarily opt in. Of a mandate, Governor Sununu explained, “It is not the New Hampshire way.”

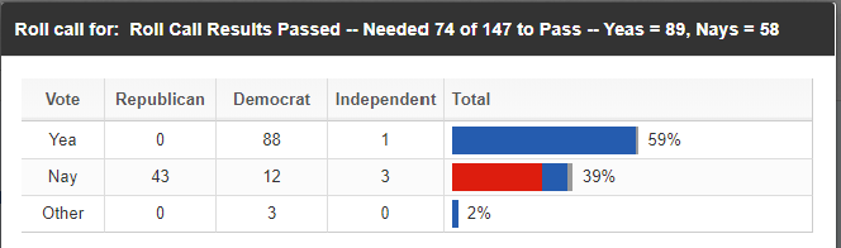

Last week, the Governor of Vermont, Phil Scott, vetoed a paid family leave bill that had made it through their legislature with enough votes to pass, but not enough to override his veto.

The bill had been introduced last year on January 29, 2019, and was held over to be taken up again at the start of their 2020 session. In order to gain more votes in their Senate, concessions had been made that caused consternation among advocates who objected to the elimination of temporary medical disability from the mandate – making it voluntary – in an effort to lower cost estimates.

As reported by Vermont Biz, the Governor, who has made previous calls to veto legislation that he cannot support, explained in a press conference,

“For years, Vermonters have made it clear they don’t want, nor can they afford, new broad-based taxes. We cannot continue to make the state less affordable for working Vermonters and more difficult for employers to employ them – even for well-intentioned programs like this one. Vermonters can’t afford for us to get this wrong, especially at their expense.”

The governors of Vermont and New Hampshire last fall had proposed a joint state plan that would be voluntary and rely on private insurance carriers, but it was rejected by advocates as being unsustainable and insufficient. They considered it unsustainable given that uncertain participation might make premium affordability unreliable, and insufficient as it would provide wage replacement at only 60% which, while bringing down costs, may make it more difficult for low-income workers to take advantage of the leave benefit.

Governor Phil Scott continues efforts on a program that would not require a mandate.

Often missing from the discussion is that the robust programs that advocates favor lean on cost projections supported by unreliable data and experience from the states that have been offering paid family and medical leave. Many who are familiar with the complexities of these evolving, broad state-run policies don’t share advocates’ confidence that premiums will have predictable growth patterns. Rising citizen awareness and familiarity with the concept and policy provisions, as well as the impact of program expansions -including the modification of provisions that erode mechanisms moderating use, together threaten to swell use rates, costs, and subsequently, the payroll taxes required of workers to sustain the program.

Is One Path Enough?

Is One Path Enough?